SURVIVAL AGAINST AN ICY WILDERNESS

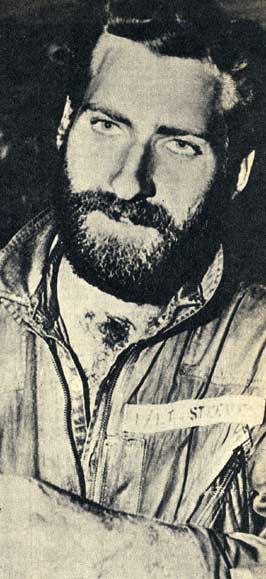

LIEUTENANT David Steeves grinned confidently. Giving a cheery wave to his fellow flyers on the tarmac at Hamilton Air Force Base in California, he walked with brisk steps to a Lockheed T‑33 jet training plane waiting on the runway.

The sun, beating down from a brilliantly clear sky, glinted on the fuselage as Steeves climbed into the cockpit and closed the transparent canopy above his head.

Before him was a mass of switches and dials controlling the plane's powerful jet engine, with its thrust of over five thousand pounds. Meticulously, Steeves went through the take‑off procedure. Over his headphones, he heard the base flight controller giving him clearance for take off. Taxiing into the wind, Steeves began his trip along the runway and eased the Lockheed into the air.

Swiftly, the ground fell away as Steeves climbed to 38,000 ft. (over 11,000 metres) and levelled off. Twenty‑three year old Steeves' was one of the base's most promising pupils, and on this May day in 1957, he prepared to enjoy this training flight in his two‑seater Lockheed.

Below him, the Californian countryside whirled and rose and fell as he went through his training programme of turns, dives and climbs. Soon, he was over the High Sierras, a vast range of mountains which extends over hundreds of miles. Among them is America's highest peak, Mount Whitney. Even in the springs of California, it was winter in the mountains . . . a wilderness of ice and snow.

Everything was going swimmingly. Then, without warning, it happened!

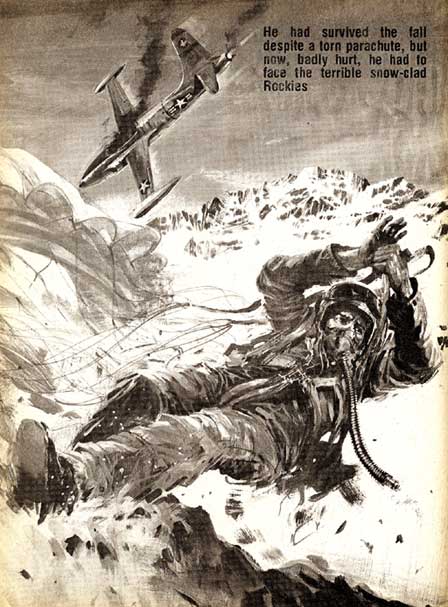

An explosion .suddenly tore the little jet training plane apart. Steeves slumped forward in his seat, knocked into unconsciousness by the powerful blast. With the limp pilot supported by his straps, the plane began to spin helplessly towards the treacherous mountain peaks a long way below.

MIRACLE ESCAPE

Steeves slowly regained consciousness to find himself in a cockpit full of smoke with his plane spiralling earthwards. Instinctively, Steeves dived for the controls and, for a few vital seconds, he fought to regain mastery of his aircraft. But his efforts were fruitless.

Knowing that his only chance of survival

was to eject, Steeves jabbed at the appropriate button and, a split

second later, was hurtling out of the plane. His parachute opened and he

began falling to Earth . . . too fast. Gazing upwards at the canopy

billowing above him, Steeves saw that two of its panels had been ripped.

Hardly had this registered on his brain, before he hit the mountainside with such force that he sprained both his ankles and slithered into a cushioning snowdrift. Fighting the pain, Steeves staggered into a sitting position and began to take stock of his situation.

He was wearing a light summer uniform that gave little protection against the north‑eastern wind that sliced into him like a knife. All around him was a wilderness of ice and .snow. For his survival, Steeves had only a service revolver, two half‑used books of matches, a little money and, his treasured possession, a photograph of his wife and baby daughter.

Blue with cold, Steeves crawled behind a rocky ridge for shelter, wrapping his parachute around him for warmth. For three days and night he remained there. From time to time, he looked at the picture of his wife and daughter and knew that if only for their sakes, he had to get out of the icy waste alive.

Any hope of being found by planes from his base faded on the fourth morning. Steeves knew that he had to make his own way back to civilisation. Fighting the pain, he pulled himself to his feet, drew his parachute about his face and began staggering along the snowy mountain trail. At night, he dug a bed in the snow and snuggled down in it. Each day, the same process was gone through . . . again and again.

CABIN IN THE CANYON

For two weeks, the routine remained unaltered until, on the evening of the momentous 14th day, Steeves stumbled into a huge rocky canyon, its sheer walls reaching skywards. Within their protection was a cabin, built of logs by a hunter. Staggering inside, Steeves found a life‑saving supply of food. Tins of beans and ham, sugar and a packet of dried soup . . . it was more than he had ever dared to hope for.

Fortunately, Steeves carried a knife, and with this he opened the cans and had the best meal of his life. Afterwards, content at last, he found some sacking to make a bed and fell deeply asleep.

Morning brought bright sunshine, and Steeves saw that his supply of food would soon be exhausted. He would have to follow the example of the man who had built the cabin and become a hunter, for there were deer in the canyon.

To catch the deer, Steeves built a trap with his revolver connected to a trip wire. It worked one morning when Steeves was too deeply asleep to hear it. Mountain lions had eaten most of the carcass by the time Steeves got to it, but there was enough meat left for him to make a meal of it -- raw.

In this fashion, Steeves managed to survive in the wilderness, eating what he could catch and drinking melted snow. Each day, he was getting fitter and stronger and, by the thirtieth day, he felt sufficiently recovered from his ordeal to try to reach civilization.

Off he set across the side of the mountain, not knowing whether he was taking a route to civilisation or more trouble. He struck the latter when he found his way out of the canyon barred by a crashine torrent of water, turned into a fast‑flowing death trap by the melting snows.

It was clearly impassable, and Steeves

made his way back to his cabin and rested again. But still freedom

beckoned, and eventually on 30th June he was in a fit state to set off

again. This time, he travelled in a different direction.

Luck was with him for, on the following day, he was spotted by two hunters warming themselves and having a meal by their camp fire. The figure which stumbled towards them looked like a long lost castaway. Steeves' cheeks were sunken and streaked with thorn cuts, and his clothes had been ripped to shreds.

But after 53 days on the mountain, injured and without much hope of being found again, Lieutenant David Steeves was safe. His days of horror in the wilderness were over.

Article and pictures

©

LOOK AND LEARN

No. 773, 6th NOVEMBER, 1976.

|

|

Reproduction of © LOOK AND LEARN article by kind permission of Laurence Heyworth |

|